Orchestrated by the Congregazione de Propaganda Fide and carried out by the religious orders, the activity of the missionaries created a dense network of relations that connected Rome to the entire globe.

The Salus Populi Romani, disseminated through engraved and painted copies, was reproduced in various cultures and in different media, as attested by a 17th-century Chinese scroll, while celebrated works of the Catholic Counter-Reformation like Stefano Maderno’s Saint Cecilia (Rome, Santa Cecilia in Trastevere) were circulated by missionaries through printed replicas, which spawned further copies like the one by the artist Nini at the Mughal court.

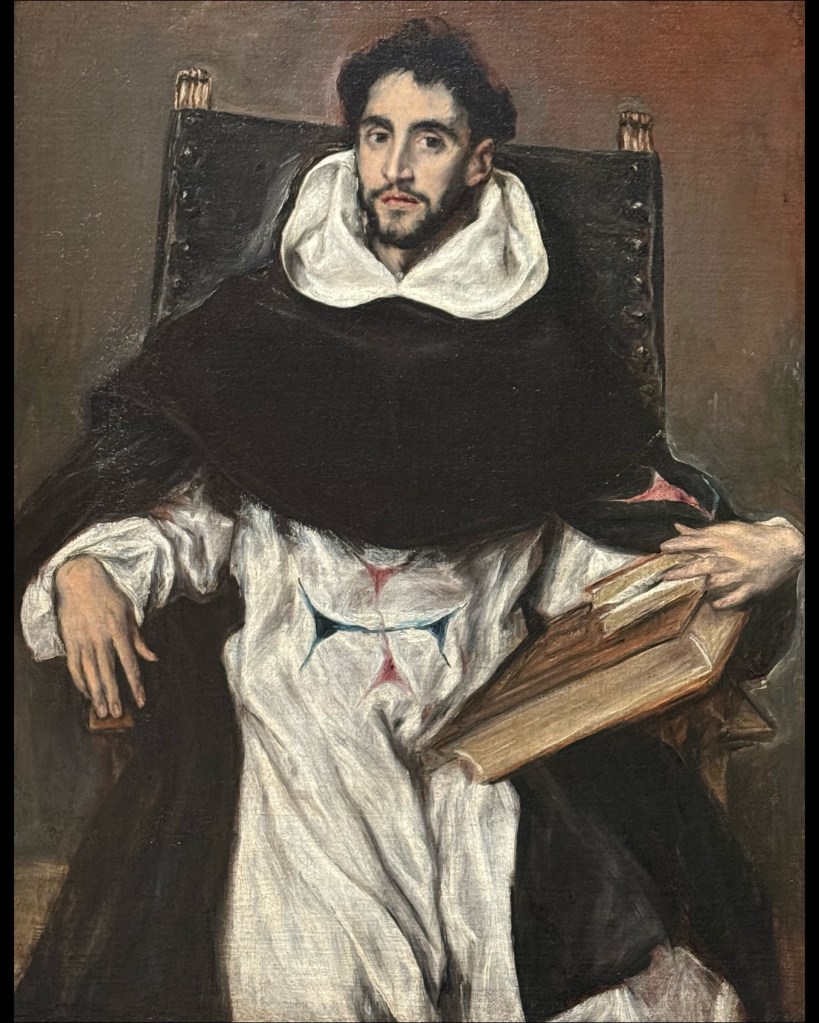

The French Jesuit Nicolas Trigault, portrayed in traditional Mandarin dress by the studio of Rubens in 1617 before setting off on his second mission to China, embodied these complex relations to the full. Although he was not Roman, before departing, in 1615, he stayed in the city to prepare the mission and to publish a volume of writings by the Jesuit Matteo Ricci, which he dedicated to Pope Paul V.

As well as the circulation of Roman images around the world, this period also saw the canonization of saints born in or related to cultural contexts beyond Europe, like, for example, Saint Rose of Lima, a Peruvian who had a notable impact on the imagination not only of her own people, but also in Rome itself.

🎨 Hieronymus Wierix (1553 – 1619), after Francesco Vanni (1563 – 1610), Death of Saint Cecilia, 1599 – 1605.

Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of Nicolas Trigault, XVII century.

Lazzaro Baldi (1624 – Roma, 1703), Ecstasy of Saint Rose of Lima, XVII century.