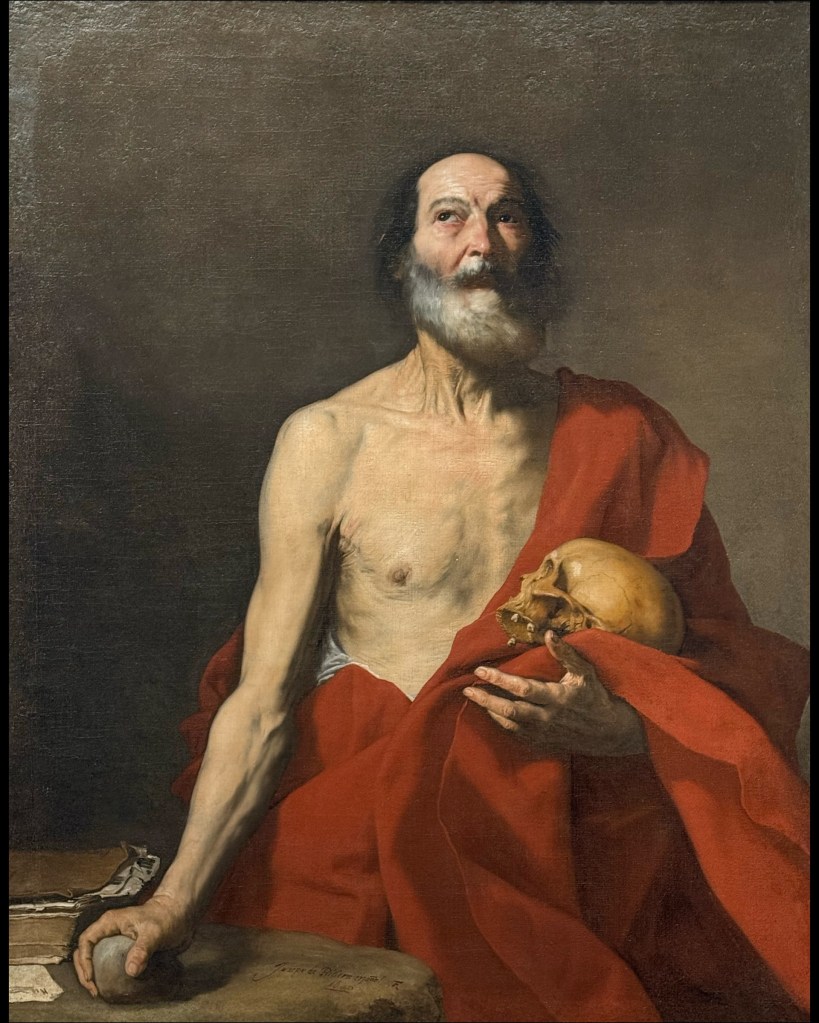

The Latin inscription at the bottom of the painting denotes its links with Rome and the importance of the work, as clearly demonstrated by its place in Ribera’s oeuvre. Born near Valencia, Spain, where he trained, he moved to Italy at an early age. After a fruitful stay in Rome, where he discovered Caravaggism, he settled permanently in Naples, a Spanish stronghold. “Lo Spagnoletto” was the most important Neapolitan painter of his time, working for both the clergy and the local nobility, as well as for Spain.

In this now classic composition, the sculptural presence of the two saints and the influence of Caravaggio, visible even in the naturalism of the dirty fingernails, are particularly admirable. Ribera painted directly, without preparatory drawings, reusing a canvas that had already been used. The rendering of the shadows and textures is masterful.

The two saints were martyred on the same day in Rome. United by the intensity of their gazes, the two founding fathers of the Church, recognisable by their attributes, are depicted in a belligerent attitude: Saint Paul, brandishing his sword in front of his open book, faces his superior Saint Peter, armed with his key and dressed in his ochre-brown cloak, symbol of revealed faith. Thus, maturity and old age, nobility and the people, doctrine and order are contrasted. Avoiding staticity, Ribera demonstrated his virtuosity in composition thanks to the depth given by Saint Paul’s arm. The still life of the books attests to the young artist’s mastery and the place these pillars of the Catholic religion occupied.